In a shocking repudiation of the Republican and Democratic establishments, Donald J. Trump was elected president of the United States in one of the most divisive elections in US history.

Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton, an upset on the scale of the UK’s Brexit decision to leave the European Union five months ago, triggered a more than 4% plunge of US stock futures in Asia and is likely to rattle American alliances and test the social cohesion of the US itself.

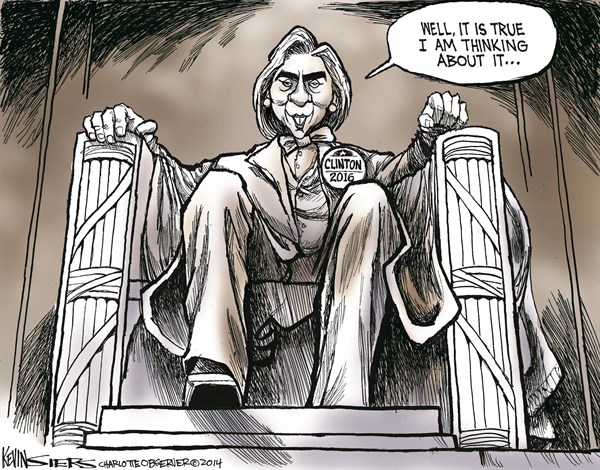

In winning, Trump denied women a historic milestone—the US presidency for the first time.

Judging by his campaign, a Trump administration will carry out one of the darkest agendas in US history, rivaling Richard Nixon for a stated intention to mete out revenge against enemies domestic and foreign. Trump has vowed to seek a special prosecutor against Clinton, go after the media, expel over 10 million undocumented immigrants, marshal funds to punish disloyal Republicans in elections, and sue women who have accused him of sexual abuse. In response to the outbreak of police shootings of unarmed black men, Trump said he would side with police and impose “law and order.”

Trump has said he would tear up and renegotiate the country’s trade agreements, the country’s landmark nuclear deal with Iran, force NATO allies to pony up cash or lose US protection, and revive torture of terrorist prisoners. All in all, a Trump adviser said the idea was to“erase” the Barack Obama presidency with executive orders in the first day in office. That would include signature Obama achievements—Obamacare and his climate change agenda, both of which would go. Trump will also have the opportunity to reshape the Supreme Court for decades to come, with deep implications for such touchstone issues as abortion rights and gun ownership.

Meanwhile Trump promises to forge a better relationship with Russia, which until now the Pentagon has called America’s no. 1 enemy. The election could be extremely positive for Russian president Vladimir Putin, and his strategy of weakening NATO, and having a much larger, more accepted role in international affairs.

Despite all this, Trump’s campaign exhortation to “make America great again” and “drain the swamp” prevailed. His victory repudiated Republican orthodoxy, which was that the party needed to embrace Latinos and young voters to win. Trump bet big that he could insult Latinos, women, Muslims, and many other groups, and win on the support of non-college educated whites who have suffered mightily by the forces of globalization. Pollsters were skeptical, and conducted surveys that validated Clinton’s strategy of overwhelming Trump by winning a large majority of blacks, Latinos, and college-educated whites.

All along, Trump had forecast that his strategy would prove the polls wrong, and it did. Until polls closed on election day, every major polling firm had projected Clinton as a victor. Trump built much higher margins in Republican areas of the country, and captured traditional Democratic states. Notably, Clinton did not campaign at all in Wisconsin since winning the Democratic nomination, and visited Michigan once—four days before the election; she appeared to lose both states.

There has never been, and may never again be, an American presidential election quite like 2016.

The 18-month-long campaign was roiled by turbulence: a newly emboldened Russia, whose cyber-spies, according to US security officials, hacked and leaked Clinton’s emails in an effort to sow election chaos; the strange behavior of FBI agents who scrutinized the emails—publicly—until two days before election day, seeming to shake up the late polling numbers; and most of all, the behavior of Trump himself, the puffed-up real-estate-developer-cum-TV-personality who mowed down 16 better-spoken Republican primary opponents, and then Clinton, one of the nation’s shrewdest politicians.

Why did Republican voters flock to this profane, womanizing, intellectually pedestrian septuagenarian who flouted long-held party tenets and social courtesies, and by one count was truthful less than 40% of the time? And what did it say about Americans that Trump defeated the combined might of a billion dollars—twice his spending—an army of Democratic Party organizers, the defection of a bevy of senior Republican turncoats, the musicianship of Beyonce and Bruce Springsteen, and the oratorical genius of Clinton’s husband, Bill, Obama, first lady Michelle Obama, and vice president Joe Biden?

“The nightmare is really just beginning for political scientists. We’ll be reviewing 2016 papers for the rest of our careers,” Christopher Hare, a professor at the University of California at Davis, tweeted on Nov. 6.

Some of the campaign’s most troubling aspects, certain to be a primary subject of scholarly study, are the social pathologies surfaced by the Trump campaign within large swaths of the white US: a language of hatred and diminishment against African-Americans, Latinos, Muslims, Jews, and women that much of the country regarded as unacceptable.

Though this anger is not purely American, but universal—seen in derogatory descriptions of Chinese in Germany, for example, and racism against Moroccans in the Netherlands—it may be more disorienting in the US, given its self-image as a nation of immigrants and example of democracy to the world.

For establishment Republicans, this presents a moment of reckoning: Will they make peace with Trump and their new irate working-class white core, or spin off into the first new major US political party since the 19th century? The indications are that such a rupture is already underway, with leading Republican intellectuals making plans to leave the party. But Republicans’ broad victory in the elections will presumably limit any splintering.

It was about the beginning of the year when it became plain that Trump’s candidacy might not be the harmless joke that many presumed. But no one guessed just how far he would veer the country off the track most were expecting.

We were prepared for a different election. For starters, Jeb Bush was supposed to ease through the Republican primaries, and then join with Clinton—who also ostensibly would cruise through the primaries—in a tough battle of the American political dynasties. Earnest and smart, a Spanish-speaking cosmopolitan (his wife, Columba, was born in Mexico) with the Bush pedigree, he was thought to be reflective of what the Republicans needed after losing the popular vote in five of the prior six presidential elections. So certain was his anointment that establishment Republicans anted up a whopping $150 million to be part of the winning ticket.

The first signs of trouble were the 16 Republican governors and senators who, unimpressed by Bush’s anointment, joined the race for the nomination. The second sign was how shrunken and whiny Bush appeared alongside them, especially next to Trump. When Trump called Bush “low energy,” and Bush merely stared at him like an incredulous and defeated schoolboy, we knew it was over. After just three state primaries, Bush called it quits. By May, everyone else had dropped out too, leaving Trump the presumptive Republican nominee.

The Democratic primaries were also not quite the predicted coronation of Clinton. She faced a surprising and stubborn upwelling of leftist populism from senator Bernie Sanders, a Vermont socialist. That turned into more like a gladiatorial contest, from which Clinton emerged the wily and resourceful victor. But it did not eliminate the threat Sanders represented—Clinton now would face Trump, whose base of support fed on the same anger as Sanders’.

This unexpected and potent undertow is a raw discontent that runs through the American populous, cutting across demographic groups and party affiliation. An abstraction missed by most, it required Trump’s and Sanders’ keener political antennae to detect, and their unscripted authenticity to capitalize on it.

Cornell Belcher, a former Obama pollster and the author of A Black Man in the White House: Barack Obama and the Triggering of America’s Racial-Aversion Crisis, attributes the white revolt to eight years of a black president and the specter now of a woman in the White House. “They see politics as a zero-sum game. In a very tribal way, they gain while others lose,” Belcher said in an interview. He called Trump a successful embodiment of George Wallace, the racist governor of Alabama who ran four unsuccessful presidential campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s. “Forty years ago, George Wallace couldn’t win the nomination. The modern George Wallace can because the wolf is at the door for those who play the tribal game,” Belcher said.

Five years ago, Chris Arnade, who has a doctorate in physics and was a Wall Street hedge fund trader for two decades, quit and began to travel to the communities we now know as Trump country. In searing detail and vivid photographs on Twitter and Medium, Arnade has chronicled what he’s found—beaten-down people who describe an unfair bifurcation in which Wall Street banks are bailed out, and heartland factories permitted to close and blow away. He came to call such folks “back-row kids,” as opposed to “front-row kids” like himself, people with a front row seat in the economy and life generally. Then Trump came along. “When Trump entered the race, I watched as his message resonated with many white, less-educated voters. He was talking to the men and women I had met on my wanderings; he told them he would restore their sense of pride,” Arnade wrote on Quartz. Arnade went on:

Most of the front-row kids, the press and politicians, initially underestimated Trump’s influence because it came wrapped in racist scapegoating. His racism, his wall [between the US and Mexico], and his anti-immigration stances were primarily an appeal to prejudice, but he was also making an attack on the globalization that front-row kids had embraced—and, in this way, attacking us. He was mocking us, and the back row loved it when he mocked us. Where we saw outlandish and boorish behavior, his supporters saw a rebel shooting spitballs at the smug front-row kids.

These voices, Trump’s undeniable electoral success, along with the shocking epidemic of police violence against unarmed African-Americans; the migrant crisis in Europe; and Brexit, all combined to at last jolt awake the mainstream to the great disgruntlement.

There is precedent for what we are watching. For a divided country, there probably is no better American analogy than the campaign of 1860, which elected Republican Abraham Lincoln, and led immediately to the Civil War. It is difficult to think of any more riven time between then and now: Trump’s routine claims of a rigged system and that Clinton is a criminal whipped his supporters into the belief that she would have been an illegitimate president.

There is also a conspiratorial bent in history. In ads and at his latest rallies, Trump repeated his claims that marauding hordes of Syrian refugees are massing to overrun the US, and that “international banks” are meeting secretly with Clinton “to plot the destruction of US sovereignty.” Such has been the fevered state of mind back to the beginnings of the republic. In his iconic 1964 article in Harper’s, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics“, Columbia University professor Richard Hofstadter said Americans have been extraordinarily conspiratorial at least since a hysteria over Bavarian Illuminati at the end of the 18th century. But Americans are not alone with this malady—Europeans have been seeing plots since millennial sects in the 11th century.

To read Hofstadter’s 52-year-old essay today is to hear Trump. Of the middle 1960s, he writes, “The modern right wing … feels dispossessed: America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they’re determined to try to repossess it and to prevent the final destructive act of subversion. The old American virtues have already been eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals.” And this, a preview of the digital age to come:

Important changes may also be traced to the effects of the mass media. The villains of the modern right are much more vivid than those of their paranoid predecessors, much better known to the public; the literature of the paranoid style is by the same token richer and more circumstantial in personal description and personal invective.

When and where did the Trump movement itself begin? In the 1950s, conservative writer William F. Buckley launched the modern Republican Party by jettisoning the hard-edged racists and conspiracy-thinkers on its margins, and finding a hard core around small government and anti-Communism. That held all the way through presidents Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush. The inflection point to the new, chaotic, and obstructionist Republicans is Sept. 27, 1994, when then-congressman Newt Gingrich led the signing of the “Contract with America.” Some 367 Republican candidates for Congress promised, if enough of them won election to overturn a four-decade Democratic hold on the House, they would embark on a conservative legislative revolution in their first 100 days in office. They won 54 House seats, taking control of the chamber, and embarked on an all-out war with then-president Bill Clinton that continued through his impeachment four years later.

More recently, this strain of Republicanism found voice in senate majority leader Mitch McConnell’s pledge to block Obama’s entire agenda.

These two acts, and numerous ones in between, had a common thread, which was that compromise with the other side was more or less treason. It was either your own ideals, or nothing. Rich super PAC groups punished any legislators deemed disloyal to this agenda by financing opponents within the Republican party to unseat them in primary races.

Trump pushed the narrative much further, though. “Hatred of ‘the other’ has grown exponentially,” Doris Kearns Goodwin, the presidential historian, told the New York Times. “It started with the Clinton impeachment, then the hatred of Bush, then the hatred of Obama. [But]…it’s of a different level when you say, ‘Put [Clinton] in jail.’”

Did Trump sit down with any fired steelworkers for a beer? Did he share a hotdog with an out-of-work coal miner? Did he do much of any of the meet-the-ordinary-folks retail politics regarded as essential in a modern political campaign? There is a much-distributed photograph in which Trump ate a pork chop on a stick at the Iowa State Fair in August 2015, and another (above) of him eating a taco bowl at Trump Tower for Cinco de Mayo this year. “I love Hispanics!” he tweeted. But that was about it. (Trump said he had never touched alcohol in his life).

Yet his snubs of these rites of every campaign did not seem to matter. Nor did the probability that he has paid no federal income taxes for at least 18 straight years starting in 1995. Trump took a substantial hit from the Republican establishment, and many other members of the party, when a 2005 tape surfaced in which he spoke of freely kissing and grabbing women “by the pussy.” It hurt him when he lashed out at Khizr and Ghazala Khan, the “Gold Star” parents of an Army captain son, Humayun, who was killed in Iraq. The Khans had criticized Trump in a speech at the Democratic National Convention. But that opprobrium never took hold among his base—Trump drew the same massive, adoring crowds wherever he went. His gambit was that he could reject not only retail politics, but also the conventional wisdom—that, if Republicans were going to reach the White House, they had to attract more Latinos and young people.

Instead, he would win on the backs of resentful whites without a college education. He would whip them into a fury with talk of Mexican rapists, stolen jobs, thieving China, corrupt reporters, claims that were comforting to his crowds, who would boo and bad mouth the assembled press corps themselves.

It was not a totally batty strategy, since somewhere between 23% and 30% of voters in the 2012 election were white, non-educated men 45 of age or older. The trick then would be getting them out to vote, and then adding on some other demographics to that foundation. Trump began just such an outreach.

Trump discussed running for president for three decades. But he only began to build up an actual campaign in February 2015, when he hired staff in Iowa and New Hampshire, the two early voting states. Four months later, he made his official announcement at Trump Tower in New York. But to say his was a streamlined operation was generous. Basically, he had about a dozen main people working with him, although he claimed there were a hundred. In terms of senior campaign people, Trump was the only person with authority. “I’m the strategist,” Trump told New York magazine writer Gabriel Sherman.

Few people thought Trump had any chance. But Trump had a secret weapon—an aide who according to Sherman monitored thousands of hours of talk radio and emerged with a set of grievances that reliably sent conservative audiences into frothing paroxysms of hysteria: immigration, Obamacare, and Common Core, the education program started by former president George W. Bush.

So it was that this intelligence became Trump’s winning script, the origin of his signature vow to build a wall across the US border with Mexico, and the rest of his main stump speech that he has used ever since. According to Sherman, Trump also deliberately stoked racial and misogynist tensions—vowing to ban Muslim visitors to the country, for instance—because, again, the talk-radio listener base more or less felt that way, and also regarded “Hillary as the world’s most horrible ballbuster.”

Trump’s positions dragged the Republican Party from its roots. At once, it was pro-gay and no longer hawkish—it was anti-intervention and, contrary to a decade and a half of orthodoxy, thought that American involvement in the Middle East was madness. Trump went against decades of bipartisan opposition to Russia’s foreign adventures, declaring that America’s best policy was to try to work with Moscow. That on its superficial face was not a bad idea, but in practice meant potentially surrendering decades of established American values, including the support of democracy and civil rights abroad. With both the Mideast and Russia, Trump abandoned the high ground held by Republicans for decades—that they and only they were tough enough to confront and deal with the ruthless Russians and terrorists.

Yet he undeniably held crowds spellbound. By the end of some two years of rallies around the country, Trump had addressed hundreds of thousands of Americans who had collectively stood for hours, waiting for sight of his private Boeing 757, emblazoned with the big TRUMP, and whooped in near enrapture until the moment he was gone. And cable and network television had given him a scale of coverage for which an ordinary candidate would pay a fortune in advertising, and why not—Trump boosted their ratings, allowing them to charge sky-high advertising rates, and thus earning them tens of millions of dollars. In the three debates—in which, for the first time anyone can remember, presidential rivals refused even to shake hands—viewership was similar to a major sporting event.

But Trump’s message did not universally resonate. In Wisconsin, for instance, where humility goes a long way, there was a feeling among Republicans that “he’s not one of us,” as one man told the Washington Post. Why? Another told the newspaper, “I’m a husband and a father. And I can’t convince myself to vote for a person who is weakening the fiber of the country.”

Trump also kept antagonizing more than half the American electorate—women. Trump may never have said explicitly that no woman is qualified to be president, but he did suggest so. In the presence of a reporter from Rolling Stone, for instance, he guffawed at the notion of a president Carly Fiorina, his rival for the Republican nomination.”Look at that face!” Trump exclaimed, seeing Fiorina on the TV news. “Would anyone vote for that? Can you imagine that, the face of our next president?!” As for Clinton herself, he said her support was all gender based—“if Hillary Clinton were a man, I don’t think she’d get 5% of the vote.” Obtaining women’s votes, he seemed to be saying, was sheer hucksterism; it wasn’t to be taken as seriously as obtaining a man’s vote.

As a character, Trump was not a complete mystery to Clinton, and not only because she socialized with him occasionally in New York. This was because her father, Hugh Rodham was not dissimilar in his hot, indiscreet temperament; were he alive today, Rodham, a Republican, might be seriously torn whom to vote for.

One of the public’s earliest recollections of Clinton is, in Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, her telling a reporter who wondered what she was doing so aggressively on the campaign trail, “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas.” But Hillary Clinton explained that she instead wanted to pursue law and a public life, as she was trained. Why Clinton should have said anything different was somewhat puzzling—what was wrong with a woman whose Wellesley classmates back in 1969 said she was likely to be the first woman president, who went on to be a partner in Rose, Arkansas’ most prestigious law firm—what was wrong with her stating flatly that she did not intend to stay home, but was going to do what she could in public life?

Yet, the popular take on the episode is that Clinton needed to quiet down, and stay in the background, which is what she did, again and again, during her husband’s political career. In a sympathetic profile in the New York Times Magazine in October, writer Robert Draper portrayed Clinton as a trail-blazer who is self-protective only because she has been forced to by public mores.

This popular caricature of Clinton as a radical and scheming climber prepared to say or do anything in order to reach the White House has stuck. But for me, there is the little color photo that hung in the dining room of my uncle’s apartment at a New York nursing home. It is of my cousin Sara’s Bat Mitzvah in 2005. Standing next to her is a beaming Clinton.

How is it that the then-senator from New York ended up at my cousin’s Bat Mitzvah? Her mom—my first cousin, Nancy—was a volunteer in a Clinton’s office. One night in 2003, there was a blackout, shutting down train service. She needed a ride home, and ended up with an offer to ride with Clinton. On the way, Clinton did some interviews on her cell phone, and borrowed Nancy’s when the juice ran out. Then at once she was done. “Now tell me what’s happening with you,” Clinton asked. Nancy poured out her soul about the blues of a difficult divorce. Clinton was sympathetic, but also tough—she bucked Nancy up, letting her know she could do just fine on her own. They ran into one another at New York political events over the subsequent years. At one, Sara handed Clinton an invitation to her Bat Mitzvah. Which was how she ended up in that photograph. “Having her there really made me feel like I was worth something,” Nancy told me.

Nancy was neither in Clinton’s inner nor her outer circle—she was in no circle at all. She is not a wealthy campaign contributor. Clinton has had nothing to gain from her attentions, apart perhaps from giving my cousins an unforgettable memory–and that photo proudly hung by my uncle. But it’s not an unusual story—her Wellesley classmates recall kindnesses when Clinton was a Republican teenager, personal touches recounted again and again by friends, acquaintances, and colleagues over the decades.

Yet this Clinton has not reached the public. In a Washington Post poll published on Nov. 2, a significantly higher percentage of likely voters said Trump is more honest and trustworthy than Clinton—he beat her on this question 46% to 38%. This is despite the newspaper’s finding that Trump out-and-out-lied in 63% of the 91 public statements of his that it fact-checked; Clinton lied in 14%.

There was reason for the broadly held distrust of Clinton, which was partly because of her problem with expressing remorse when she does have a lapse. Her mind-boggling use of a private email server while secretary of state comes to mind. In an email released by WikiLeaks, Neera Tanden, a member of the Clinton coiterie, described her inability to apologize for such episodes as “like a pathology.”

Trump overcame considerable odds to win. Against the hostility of his own adopted party, lacking a personal political organization, and relying on an untested political strategy, Trump muscled his way to power with panache in front of crowds, and a practiced ability to rip apart debate opponents with the sharp insult. Trump seemed to be weighed down by his tremendous personal problems—his defensiveness, a tendency to lash out, and only an elementary understanding of foreign affairs. But in the end, none of that seemed to matter.

Hans Noel, a professor at Georgetown University, said Trump, by pushing up Republican turnout in places where they had been lacking, defied polling models that rely on data from past elections. Ultimately, Trump did what he said he would, which was “to alter the map,” Noel said. “A lot of that talk was about California and New York, which did not move. But Michigan and Wisconsin have a lot of the less educated and white voters that Trump has been reaching out to, and that is a big shift.” Noel said that this may indicate a long-term shift, which has serious implications for future Democrats.

In addition to Trump’s victory, Republicans held onto the Senate and House, meaning that one question is how Democrats respond to a full-throated Republican agenda. When it appeared that Clinton would win, it appeared that the country—and Washington in particular—might not be governable, at least any time soon. In the FBI’s New York office, there was a reported uprising in the form of a demand for a full-out investigation of the Clinton Foundation. All of this was talk—nothing was known with certainty. But if true, it seems likely to go ahead.

Democrats seem likely to do everything they can to stop the Republicans, though there is not much they may be able to do. A Trump Justice Department could follow through on Trump’s vow to investigate Clinton personally.

If so, the FBI will be channeling a feeling across the heartland, where Trump and many other Republicans were maintaining a drumbeat that Clinton was a criminal and, if she won, would be illegitimate. At Virginia’s Robert E. Lee High School, the principal arrived at school on Nov. 1 dressed as Trump, standing next to his vice principal made up as Clinton, wearing an orange jump suit and restrained by waist cuffs.

Close up, both sides felt the stakes were existential—that the country might not survive as they knew it should one or the other leader reach the White House. But it may require the distance of time and event to know who, if either, is right. The question is not academic—historically speaking, fascism has sometimes resulted when populations have lost faith in the integrity of their basic institutions, and they divide into extremes who demonize one another. It is the conditions that pave the way for the dictator, rather than the opposite.

To call the long campaign an embarrassment to all Americans is to seriously underplay what we just watched, the incalculable impact on our national psyche, and the damage to our international prestige. This is not funny, folks.

For all his over-the-top machismo and scatological references, Putin, for instance, has never boasted about the size of his penis, at least publicly, as Trump did in a nationally televised debate. For all his power grabbing in China, Xi Jinping has never said of a critic, “I’d love to punch him in the face.” Again, at least publicly.

“The ‘alt-right’ forces that Trump has tapped into, given voice to, and in a sense licensed to change the nature of political discourse (the more explicit use of personal insult, racial insensitivity, etc.), will be difficult to put back in the bottle,” said Mark Peterson, a professor at UCLA.

Beyond discourse, with a Trump presidency and Republican control of Congress, there could be little resistance to a rapid reorientation of America’s basic stance on key domestic and global issues. Supreme Court openings will offer additional opportunities for a generational shift. And Republicans wield complete control of the executive and legislative branches of 23 states, and the governorships of 31 states. Trump’s followers could pursue additional change there.

Donald Trump promised a Brexit-style victory and he achieved just that.

The world woke up today to the shock news that the Republican candidate beat Hillary Clinton, the first female major-party candidate to run for the US presidency. In claiming this victory, Trump stumped the majority of pollsters and political commentators, who expected women to carry Clinton to the White House.

So, what exactly happened? Women did vote overwhelmingly to elect Clinton, but it was white women who helped hand Trump the presidency, according to Edison national election poll.

Overall, 54% of women voted for Clinton, much higher than the 42% of women who voted for Trump. But when the women’s vote is divided by race, it becomes clear that black women actually largely drove the so-called gender gap against Trump.

The majority of non-college educated white women (64%) voted for Trump, while 35% backed Clinton. This figure is far higher than non-college educated black women, of which only 3% voted for Trump, and non-college educated Hispanic women, of which 25% voted for Trump. Black, Hispanic and other non-white women backed Clinton in far greater numbers.

Trump’s sexist rhetoric has been well-documented throughout the election; he dismissed a female moderator by suggested she must have had “blood coming out of her wherever,” called for women who have abortions to be punished (then backtracked), bragged about grabbing women “by the pussy”, and was dogged by allegations of sexual assault throughout the campaign. Yet, despite all of this, 45% of college-educated white women voted for Trump.

In comparison, only 28% of college-educated Hispanic women voted Trump, while only 6% of college-educated black women backed Trump.

The exit poll, based on a sample of 24,537 voters at 350 polling places, isn’t perfectly representative. As time passes, voter registration and census files will provide a more accurate picture of how Americans voted. Earlier this year, a New York Times analysis found that recent exit polls had overstated demographic shifts and that the electorate was whiter than expected.

In the end, it’s his white base that most benefited Trump. His most enthusiastic supporters were white men across the board, with 54% of college educated white men and 72% non-college educated white men backing him. These white men and women voted like a minority group, according to one electoral analyst, coalescing on a mission to put him in the White House.

Clinton Thought She Had Victory In Her Sights

When this race became a referendum on what it means to be an American, Hillary Clinton thought she had victory in her sights.

But voters had a different idea than the wily veteran of over four decades of American political life. In far greater numbers than expected, voters rejected her in favor of Donald Trump, an erratic tycoon whose mean-spirited campaign attracted unprecedented criticism for a major-party nominee. In the end, Clinton’s fraught history—symbolized by the baroque investigations into her private e-mail server—overcame whatever advantages her centrist agenda, critiques of Trump’s outrages, and well-funded, professionally run campaign could give her.

Soon after Pennsylvania’s 20 votes in the electoral college were called for Trump by the Associated Press early Wednesday (Nov. 9), it was clear the path for a Clinton victory had disappeared.

Indeed, Trump’s bet that white voters would turn out and surprise the pundits seems correct: Rural white voters in states that Democrats were counting on turned out to deliver for Trump, while Clinton could not find the language to win them over. Fears that she had not campaigned hard enough to defend the Democratic firewall late in the race proved true, as Trump outperformed the polls to win a series of close victories in the midwestern states, in addition to taking the key swing states of Florida and North Carolina, where Clinton failed to do as well as president Barack Obama did in 2012.

Trump owes his victory to the polarization of American politics—the final difference in the vote will likely be less than two percentage points. But enough voters ignored warnings about Trump’s threat to US democracy to propel a man who embodies some of America’s most deep-set historical vices to the presidency. Why? He promises a return to a fantastic past where the social and economic turmoil of the 21st century can be avoided.

It does not seem likely he can deliver on those promises, but voters appear all too used to politicians who don’t keep their promises. White Americans heard Trump’s voice, not Clinton’s, and came out to make him president.

Eight months ago, in Michigan, Clinton lost the Michigan Democratic primary, a surprise defeat that pollsters hadn’t been expecting and one that today seems even more telling. The victor was Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, an independent whose primary challenge would highlight Clinton’s electoral weaknesses among white voters.

Before she became the standard bearer for a movement against Trump, Clinton’s campaign—a multimillion-dollar effort with the most talented operatives and innovative tech available—had a problem explaining what she stood for. Not in terms of the issues, where Clinton’s wonky record set the tone, but in terms of, “why her, why now?”

The primary electorate was shaped by Democratic frustration with the Obama administration’s turn into deadlock. Voters were looking for something more strident than Obama’s incrementalist agenda.

The rifts in the Democratic coalition that had been mostly subsumed during the past eight years broke to the surface, as the capital-loving wing of the party with its branches on Wall Street and in Menlo Park clashed with those to whom economic recovery came less swiftly: Students and young graduates with their accompanying debt loads, and middle-class workers confronting wage stagnation.

Though Clinton carefully cultivated the influential progressive senator Elizabeth Warren to forestall her potential challenge from the left, Sanders was dead set on mounting what he thought of initially as a protest candidacy. He channeled American frustration with his endless criticisms of “the millionaire and billionaire class.” He called for major expansions of the US government to help students with their debt and workers get a fair shake. His unpolished presentation couldn’t have been more of a contrast with Clinton’s poise.

Sanders made hay of Clinton’s retreat on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a landmark free trade agreement she had backed in theory while working for Obama but rejected after its full details were made a public. Even more so, he went after her as an ally of Wall Street whose judgement was compromised by her time among the US elite, giving paid speeches to bankers that she wouldn’t share with the public. Clinton, he said, was the establishment, and what was needed was a political revolution.

Yet Sanders faced several limitations as a candidate. Despite his own history in the civil rights movement, he found it difficult to speak directly to minority voters’ concerns about racism. At a time when Black Lives Matter and police violence dominated the news, he was hampered by his overwhelming focus on economic disparities. While his rhetoric would improve over time, his inability to pull black voters from Clinton allowed her to dominate voting in southern states.

And Sanders could never quite land a foreign policy critique against Clinton despite her fraught record as US secretary of state, in part because any criticisms of her would naturally reflect on the popular president she had served.

Perhaps most notable, Sanders famously declined to make Clinton’s handling of the e-mail server she used for official and personal business during her tenure as secretary of state an issue early in the campaign. The server become public in 2015, during a series of obviously politicized Congressional investigations into the Benghazi attacks on US personnel in Libya. In June, an FBI investigation would determine that Clinton had not illegally mishandled classified material.

Sanders, unable or unwilling to deploy the most telling arguments against Clinton, soon found himself in a losing position. Despite raising more money than her campaign for several months, he could not win over enough minorities or women to break Clinton’s growing lead in convention delegates.

The Clinton team’s disciplined strategy—reflecting lessons learned during her loss to Obama in 2008—gave her a lead she would never relinquish until the final day of the race. By the time the primary cycle ended in June, she was the Democratic nominee. But critics and journalists alike, noting Clinton’s high unfavorable rating, would continue to wonder whether Sanders, a relative outsider who out-polled her with white men, could be a stronger nominee in an unsettled electorate.

Donald Trump, erstwhile Clinton supporter, emerged from the wreckage of the Republican primary as the voice of a growing nationalist movement. Rather than a conventional GOP politician, Clinton faced an undisciplined builder who had begun his campaign by insulting Mexican immigrants and hadn’t stopped since. He had no qualms about launching attacks directly at Clinton’s weak points, whether the email server or her ties to Barack Obama, still anathema among Republicans.

There was no shortage of predictions that Trump would be easy pickings for Clinton, but that belied both the strength of Republican loyalty to their party (antipathy to Clinton) and his particular strength: He emboldened a hard core of enthusiastic conservatives to express racist and sexist sentiments the Republican establishment had previously limited to dog-whistles, channelling the political voice of Pat Buchanan and building on the Tea Party and the racist backlash spurred by Obama’s historic presidency. His willingness to abandon the party’s free markets orthodoxy in favor of a welfare-for-whites approach allowed him to reach across party lines more effectively than past Republicans.

Before the two party conventions in late July, Clinton and Sanders were still repairing their relationship, and the party along with it. A haze of official sanction still trailed in her wake. When the FBI recommended no charges against Clinton for mishandling classified information on her email server, FBI director James Comey still held an unprecedented press conference to call her behavior “extremely careless.” Journalists, meanwhile, pored over the contents of the server, which showed the sometimes unsavory side of a philanthropic operation that relied on access or the illusion of access to raise money for good causes around the globe. While her critics called it corruption, there was never any evidence of a quid pro quo with any donor or associate.

The media’s obsession with the scandals and the party’s slow reunion allowed Trump to stake early leads in key polls. His raucous nominating convention in Cleveland, Ohio, was a mad four-day paean to the candidate that included the spectacle of plagiarized speeches, intra-party rivalry, controversial gay billionaire endorsees, and the truly terrifying scene of scandal-tarnished governor Chris Christie leading the crowd in chants of “lock her up.” Trump’s running mate, Mike Pence, was a sop to a nervous Republican establishment, and brought with him one of the most conservative records in the country. The event culminated in a quasi-fascistic speech wherein Trump, accepting the party’s nomination, promised, “I alone can fix it.”

He would never have a better chance of winning the election, according to poll aggregators like FiveThirtyEight, until it was clear that victory was in his hands.

Clinton’s convention was scheduled to begin just days after Trump’s ended, and organizers feared that Sanders holdouts would take over the floor to force protest votes. Emails stolen by Russian hackers and made public showed Democratic National Committee chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz had worked to back Clinton, the party’s favored nominee, over Sanders. She would resign over the conflict, adding to the pall over the convention. (Ironically, her replacement, Donna Brazile, would later be forced out of a job at CNN when further hacked e-mails revealed she shared debate questions with Clinton and Sanders ahead of time.)

The moment seemed poised for some kind of 1968-style tearing apart of the party by faction, age, and class. It didn’t happen. Sanders protesters made themselves heard on the floor from time to time, and took over a media filing center to underline their complaints about the primary. Mass conflict was averted by careful concessions made to Sanders’ camp on the party platform and in his role at the convention, a marquee first-day speech in prime time that allowed Sanders to endorse Clinton on his own terms.

But Clinton’s team took a risk: Rather than focus entirely on uniting their own party, as Trump did at his convention, Clinton’s team would adopt the more traditional tactic of using the nationally-televised spectacle to highlight the broad appeal of their candidate.

Her vice presidential pick was the moderate governor of Virginia, Tim Kaine, not a darling of the progressive movement. Bernie Sanders’ valedictory on the first night of the convention, intended to put a stamp on their rivalry, was followed by Michelle Obama, the standout rhetorical star of this election, who delivered a widely hailed speech that made the case that Trump was simply too offensive to be president.

“This election, and every election, is about who will have the power to shape our children for the next four or eight years of their lives,” the US first lady said, echoing a message that Clinton’s team would spend millions to broadcast around the country.

This convention was the ultimate big tent: New York Republican-turned-Independent mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose backing of stop-and-frisk had not made him a favorite of the Democratic base, appeared to assure moderates that Clinton was by far the better choice than Trump, even as the Mothers of the Movement, women whose children were lost to police violence, told black voters that Clinton understood the perils of systemic racism.

But this chorus of elites and minorities and progressives coming together seemed to be less than the sum of its parts on election day. Clinton underperformed Obama’s 2012 numbers with minorities, while only moving college-educated white voters toward her by a few percentage points. But more importantly, the convention seemed to miss one key constituency: White voters, especially in rural areas, who felt left behind those same elites and convinced that those minority groups were getting ahead of them in line for the American dream. Clinton’s convention appeared to have something for everyone, but very little left for working-class white voters.

The first presidential debate in late September was a final chance for Trump to change the game, the first time he would appear next to Clinton and have an opportunity to prove arguments about his erratic behavior and angry persona false.

Clinton was once again in the midst of deepened scrutiny. She left a 9/11 memorial event after feeling faint, leading to a wild surge of internet rumors about her health. She hadn’t given a proper press conference in months, leading to a barrage of press criticism (which was never matched when Trump began avoiding the press in the final two months of the campaign). Her campaign chairman, John Podesta, had his e-mail inbox hacked, and his messages leaked by Wikileaks, revealing embarrassing internal deliberations and casting more light on Clinton’s connections to wealthy individuals and corporations.

Trump, sensing his improving position, declined to prepare for his debate, beyond holding bull sessions with a coterie of disgraced politicians, generals, and even media executives, once ousted Fox News chief Roger Ailes briefly found his way into the camp. On his third set of campaign leaders, Trump became ringmaster of his own destiny.

Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, right, and Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump listen to a question during the second presidential debate at Washington University in St. Louis, Sunday, Oct. 9, 2016.

The most important moment came at the close, when Clinton mentioned Trump’s treatment of women, citing a former pageant star named Alicia Machado, who Trump had mocked as fat. Trump’s blustery response was hardly elegant, and he spent the next several days attacking Machado in late-night tweets and falsely saying she had appeared in a sex tape.

That would come back to haunt him came days later, when a video tape of Trump on Access Hollywood was published by the Washington Post. The tape featured Trump talking about his treatment of women, how he kisses them without asking and boasting he could do anything, even “grab them by the pussy.” At the next debate, pressed by CNN’s Anderson Cooper on whether he had ever done those things, Trump said no. Soon, more than a dozen women would come forward to allege that Trump had sexually assaulted them by kissing or fondling them without permission. One woman is currently suing Trump in a civil case, alleging that he raped her when she was 13 years old.

Through it all, there was no sign that Trump would change his approach to the contests. Each time he would start with a subdued mien, speaking a husky undertones, before rising to issue a soundbite—”Nasty woman!“—that would echo for days on social media. He doubled down on the alt-right influences in the campaign, now managed by CEO of Breitbart Media, Stephen Bannon. He paraded a line of women who accused Bill Clinton of sexual harassment at the second debate, and promised that he would put Hillary Clinton in jail if he were president. In the third debate, he refused to say he would accept the results of the election if he lost.

His sheer intransigence frustrated elites in both parties, and left many women baffled at his ascent. But another segment of voters appear to see him hectored by these women and, by extension, a victim of Clinton’s political attacks. Some clearly saw hypocrisy in Clinton’s criticism of Trump given her own husband’s past behavior. As Trump gave voice to resentment against new social codes that denigrate casual sexism, Trump won the overwhelming support of male voters in the 2016 election. Clinton’s name on the ballot was a red flag that attracted a bull.

A final dramatic interlude would give ulcers to her supporters. Twelve days before the election, the FBI’s Comey sent a letter to Congress saying that the investigation into the sexting habits of disgraced former Congressman Anthony Weiner led to the discovery of e-mails from Clinton’s server, likely sent or received by Weiner’s wife, Huma Abedin, Clinton’s closest personal aide.

The letter shocked the media and launched a breathless reassessment of her chances. Though the announcement contained no real content, and a week later, Comey would come forth to say that no new e-mails were found, the news provided traction to fears that Clinton’s continued political career would continue to be a never-ending parade of investigations and leaks. Republican-leaning independents and outright partisans came home to Trump, perhaps experiencing flash-backs to the 1990s and the media’s public obsession with Clinton scandals.

Indeed, Comey’s role in the campaign underscored how little attention traditional policy issues received compared to hyped-up scandals. Trump’s agenda promises little real help to those voters who backed him, but plenty of assistance to wealthy Americans. Yet there was a single issue in this race that dominated everything else, and it was this: Who is an American?

Trump’s flirtation with white supremacists, the anti-semitic nature of his campaign rhetoric, his constant bashing of immigrants generally and specifically Mexicans, his treatment of women and vision of their role in society, all made him a throwback to a time before the US debate over the virtues of social diversity.

In his criticisms of political correctness and depiction of an apocalyptic America, Trump found a constituency—of white voters in communities threatened by the all too real changes facing the United States—that Republicans had represented before but never with such alacrity. Their reaction to a changing America, catalyzed by Trump’s demagogic appeals, generated an electoral firestorm that few foresaw. Clinton’s more optimistic vision that emphasized the new picture of America clearly didn’t resonate with working class white voters who once reliably pulled the lever for her party’s previous nominees.

For all the demographic changes the United States has seen in recent years, white voters remain the largest single constituency and now, in the words of one electoral analyst, they are voting like a minority group. Trump’s ability to drive them out echoes the leverage of enthusiasm used by Obama to deliver his majorities in 2008 and 2012. The question that will haunt Democrats, at least into 2020, will be whether a different candidate—one without Clinton’s unique and overbearing history—could have held the center.

Years In The Spot Light

Donald Trump has spent decades in the spotlight, as wealthy real-estate developer, a reality-television star, and, in the past year and a half, an extremely effective political agitator, if not a smooth political operator. We know what he is like, and it is unreasonable to think that the office of the United States president will change much of it. The question now is what he will do.

The 2016 election campaign was always long on personality, and even important moments for discourse—the debates, for instance—felt woefully short on substance. But Trump has signaled his intentions on several key issues. And now we’d best start paying attention.

Immigration

Trump’s first actions on immigration will likely be overturning the policies that US president Barack Obama put in place to protect undocumented immigrants.

Under the policy known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), implemented by Obama as an executive order in 2012, more than 700,000 immigrants who were brought into the country illegally as children have been allowed to temporarily stay and work in the US. DAPA is a similar policy for the undocumented parents of American citizens; it has been challenged in court by several states.

Trump has vowed to end DACA, DAPA, and so-called “catch-and-release” policies, or the practice of not detaining immigrants while they wait for their cases to be processed. He’s also said he’s going to triple the number of US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement agents and will “move criminal aliens out day one.”

None of this will result in mass deportations in the short term—the US Department of Homeland Security does not have the funding to deport all 11 million people who are thought to be in the country illegally, and it’s unclear where Trump would get it. There’s also a question of physical resources; thousand of Central American women and children who showed up at the border in the summer of 2014 quickly overwhelmed existing detention facilities.

It would take more funds still to build that wall between the US and Mexico that Trump has talked about from the start of his campaign. Aside from being very expensive, it would require congressional approval, and logistically, it would be very complicated to erect a barrier across the length of the entire border.

But Trump doesn’t need a physical symbol like a wall to communicate his policy objectives. His tone alone will immediately destroy the fragile peace of mind that Obama’s approach had given millions of immigrants. Obama in essence had told them, if you don’t have a criminal record, we’re not coming after you. That assurance is gone under Trump.

Infrastructure

It’s no secret the US needs to invest in its crumbling bridges and highways. The backlog of infrastructure projects is expected to cost $3.6 trillion by 2020, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. The need is so stark, and the benefits to the economy so obvious, that it was one of the few areas where Trump and Clinton agreed this campaign season. But while rebuilding crumbling bridges and highways may be a smart long-term investment, it’s unclear whether Congress will have the appetite for what is essentially another stimulus program.

Trump hasn’t given a precise figure for how much he wants to spend on infrastructure, other than to say he would at least double the $275 billion Clinton proposed.

Trump says he would develop US transportation, water, telecommunications, and electricity systems, using “American steel made by American workers.” He would dangle tax credits to attract private investment and streamline permitting for pipelines and other energy projects. He is vague on how to pay for his plan, but has suggested he would issue bonds and support an infrastructure bank.

“We’ll get a fund, make a phenomenal deal with low interest rates, and rebuild our infrastructure,” he said. Then there’s the funding option he unveiled at a Nov. 7 rally, near the tail end of his campaign trail.

Obamacare

How you view Obamacare is a litmus test for your political leanings. Liberals see the program as a basic success, one that has provided millions of previously uninsured Americans with healthcare, but just needs a few tweaks. Conservatives see a disaster, with soaring premiums, failing state co-ops, and a two-tiered insurance system that is leaving many on Obamacare plans with fewer options. But both sides agree on the core problem with the current system: not enough young, healthy people are enrolling, meaning the insurance pools have too many sick patients who are driving up costs.

But whereas Clinton had promised to recalibrate and expand the Affordable Care Act, Trump has said he’ll repeal it, and end the individual mandates requiring health insurance. As a replacement, he has proposed expanding health savings accounts, which allow families to set aside money tax-free to pay for insurance premiums and drug costs, and would let them fully deduct medical expenses from their taxes. He also wants to let insurance companies sell policies across state lines, generating more competition, and would allow drugs to be imported from overseas.

Trump’s plan is mainly achieved through rewriting the tax code, which would likely need bipartisan support, and does little for low-income families who are not paying taxes. According to one analysis, the net effect could mean 25 million Americans could lose health insurance.

Trans-Pacific Partnership

One thing we know about Trump is that he isn’t for free trade. The Mexican peso has been tracking Trump’s odds of winning; when they improved, the currency frequency would plunge on the expectations that Trump will begin his promised demolition of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). You can assume that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is over, too.

The TPP, intended to cover a dozen countries and roughly one-third of global trade, promised to lower tariffs and set standards on a broad range of trade issues, from labor and environmental regulations to the treatment of intellectual property. It was potentially a counterweight to China’s strength as a manufacturer to the world.

The deal was endorsed by president Obama and, at one time, Clinton. But that was before the pact was fully negotiated, and before influential senators to the left of Clinton, namely Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, forced her into the skeptics’ corner. Trump needed no such nudging. From the early days of the campaign, his full-throated critiques of the deal helped brand it as a refutation of core American values.

His threats to hike tariffs on Mexico and China by 35% or 45% will be difficult without collaboration from lawmakers in Congress. Major US corporations will fight Trump’s trade threats tooth and nail, since every complication in the global supply chain means losses to their bottom line.

But even if Trump just uses presidential powers to punish countries for currency manipulation (whether real or perceived), a trade war could ensue. This could entail challenges before the World Trade Organization, retaliatory tariffs, and other penalties on big US companies doing business abroad—which is most of them—and would hit the pocketbooks of the American people, whether they are buying cheap goods at Wal-Mart or expensive goods at the Apple store. And a US assault on the foundations of global commerce will no doubt fray relationships with major allies when it comes time to dealing with non-economic challenges facing the globe.

The US Supreme Court

Trump made an unprecedented move in electoral politics (one of many, to be sure) this past August, when he released a shortlist of potential replacements for the late US Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia. Heeding the call of conservatives, who are desperate to prevent a liberal majority on the court, his list drives hard to the right; he reportedly consulted the ultra-conservative Heritage Foundation and Federalist Society in compiling it.

Notable names of possible nominees include conservative Utah senator Mike Lee (who refused to endorse Trump) and Charles Canady of the Supreme Court of Florida who in 1995, as a congressman, introduced the first proposed federal ban on “partial-birth” abortions. Also on the list is 10th Circuit Court of Appeals judge Timothy Tymkovich. He wrote the opinion in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, which held that privately owned corporations could not be forced to provide contraception to employees as part of health-insurance packages.

A continued Republican majority in the Senate means that whoever Trump picks to fill the court’s ninth seat will likely be quickly confirmed, reestablishing the ideological balance of the last few years: four sure conservatives, four sure liberals, and moderate-conservative justice John Roberts as the perennial tiebreaker.

Strange days lie ahead for the Democratic Party. The republicans control all three branches and will pack the Court with conservative judges that will shape the future for decades. Voters rejected the things we offered. The days of Bush and Clinton are done, last century thinking has been retired.

Face it, there are too many regulations and the American Healthcare Act is riddled with problems and was poorly written from the get-go. All the executive orders crafted by President Obama will be undone during Trumps first few days in office and the AHA faces certain repeal.

Hillary Clinton had a lot of ambition and a fierce desire to be president. Sadly she wasn't a very talented candidate. The voters viewed her as less than honest and she never took her email and private server debate on full face. Like Trump's republican challengers she had no idea how to fight and he knocked her out just as he had knocked out 16 republicans before her.

The party leadership (Debbie Wasserman Schultz) played fast and loose behind the scenes to ensure Bernie would fail and Hillary would be the candidate. The party had stacked the deck to ensure Clinton would be the candidate.

It is our responsibility as Democrats to run candidates tough enough to weather the storms and win.

Amherst Democratic News

ACVDN

Need To Boost Your ClickBank Banner Commissions And Traffic?

ReplyDeleteBannerizer makes it easy for you to promote ClickBank products with banners, simply go to Bannerizer, and get the banner codes for your favorite ClickBank products or use the Universal ClickBank Banner Rotator Tool to promote all of the available ClickBank products.