Democrats Should Fear The Republicans Courting Unions.

Republicans used to support workers and if they were smart they would again.

The GOP should not take for granted any voter group, especially unions.

There is no doubt that labor unions in recent election cycles have been seen as tentacles of the DNC octopus. But, in spite of their support for Democrats, unions have been taken for granted by that party, especially by Democrat presidents and members of Congress, and unions have not gotten the attention or results they reasonably could expect from their political support. And, therein lies the opportunity for Republicans.

Democrats have even taken to threatening unions if they vote Republican. Vice President Biden said the following at a union convention: “And don’t any of you, by the way, any of you guys vote Republican. I am not supposed to say; this isn’t political . . . don’t come to me if you do! You’re on your own Jack!”

Of course the vice president said he was joking, but I think otherwise. Unions today are seen as tools for the Democratic Party and their support is expected, not earned.

Democrats love mocking Republicans with regard to union support. They say things like: “A union member voting Republican is like a rabbit voting for hunting season to open.” I see Republicans seeking union support more like the Aesop fable of "The Tortoise and the Hare." Republicans are the tortoise, seemingly losing to the hare until, through slow and steady perseverance, they win the race.

The exit polls in 2008 found that 39 percent of voters identified from union households voted for McCain for president. The Tampa Bay Times reported that since 1952 only one other Republican candidate did as well among union voters — Ronald Reagan in 1980, who also had a gap of just 7 points between overall support and union support.

But Reagan wasn’t able to repeat his magic in 1984 — his union vote trailed his national vote by 13 points. And that pattern continued until McCain in 2008, with the gap bouncing between 11 and 13 points from 1984 to 2004.

In 2010, 49 percent of union households in Massachusetts voted for U.S. Senate candidate Republican Scott Brown over Democrat Martha Coakley.

You cannot expect support if you don’t ask for it and you do not earn it.

Unions today should be playing their points with party platforms and candidates. Knee-jerk support by unions for any one party is a disservice to union members. When Republican policies support union goals and objectives, then unions should support it. Same goes for Democratic support. Corporations in America support Republicans and Democrats when it is in their interests and unions should do the same.

The XL pipeline is a good case study on why unions got taken for granted by the present administration. Despite the overwhelming support unions have given Obama in 2008 and again in 2012, the president just this week vetoed the XL pipeline bill that passed both the House and the Senate with wide bipartisan support. CBS did a poll this past January, which found that 60 percent of Americans want the XL pipeline.

This is what the International Brotherhood of Teamsters said with regard to the need for the XL pipeline in January of 2014.

“Following the U.S. State Department’s analysis that the Keystone XL pipeline project provides a safe and correct process for the transport of Canadian oil to the U.S. Gulf region, the Teamsters Union is pleased that the project, which will directly create 20,000 good jobs for American workers, is one step closer to reality.

"The Teamsters Building Material and Construction Trades Division, affiliated with the North America’s Building Trades Unions alliance, praised the alliance’s statement urging that the pipeline project be constructed immediately.”

And in February Mr. James P. Hoffa, the general president of the Teamsters, urged Congress to pass and the president to sign an XL pipeline bill when he said, “If the pipeline is not built, important socioeconomic benefits will not be realized — the positive impacts on local, state, and federal revenue, spending by construction workers, and spending on construction goods and services.”

Republicans want to put America back to work and unions must be part of any jobs initiatives.

So, why should unions support Republicans? Here are a few reasons:

Republicans’ fiscal policies empower the worker by creating responsible budgets and tax structures that encourages job creation and retention

A day’s pay for a day's work

Government should do for the people only what they cannot do for themselves

Government should not create a government-dependent society — we should foster and encourage a robust work force

Republicans are for more domestic manufacturing

Republicans believe in international trade agreements that are fair to American workers

For the aforementioned reasons and so many more, the time has come for Republicans to stop assuming that unions are an arm of the Democratic Party, stop the knee-jerk opposition to working men and women who want to collectively bargain for better wages and benefits, and start earning the union vote the way Reagan, McCain, and other Republicans have done.

Now is the time for Republicans and unions to come together and work together for a better America.

If Democrats don't fear this they are already dead. For the last 25 years Democratic power has been on the decline. It is so bad now that a jack-off like Donald Trump has won the presidency. One thing for sure you can't keep walking down the same road you have been traveling for the past quarter century. Throw out the old ideas and make room for the young to take over.

ADD to the Creed: No interference in our election process by foreign powers.

If politicians care almost exclusively about the concerns of the rich, it makes sense that over the past decades they've enacted policies that have ended up benefiting the rich.

In 2008, a liberal Democrat was elected president. Landslide votes gave Democrats huge congressional majorities. Eight years of war and scandal and George W. Bush had stigmatized the Republican Party almost beyond redemption. A global financial crisis had discredited the disciples of free-market fundamentalism, and Americans were ready for serious change.

Or so it seemed. But two years later, Wall Street is back to earning record profits, and conservatives are triumphant. To understand why this happened, it's not enough to examine polls and tea parties and the makeup of Barack Obama's economic team. You have to understand how we fell so short, and what we rightfully should have expected from Obama's election. And you have to understand two crucial things about American politics.

The first is this: Income inequality has grown dramatically since the mid-'70s—far more in the US than in most advanced countries—and the gap is only partly related to college grads outperforming high-school grads. Rather, the bulk of our growing inequality has been a product of skyrocketing incomes among the richest 1 percent and—even more dramatically—among the top 0.1 percent. It has, in other words, been CEOs and Wall Street traders at the very tippy-top who are hoovering up vast sums of money from everyone, even those who by ordinary standards are pretty well off.

Second, American politicians don't care much about voters with moderate incomes. Princeton political scientist Larry Bartels studied the voting behavior of US senators in the early '90s and discovered that they respond far more to the desires of high-income groups than to anyone else. By itself, that's not a surprise. He also found that Republicans don't respond at all to the desires of voters with modest incomes. Maybe that's not a surprise, either. But this should be: Bartels found that Democratic senators don't respond to the desires of these voters, either. At all.

It doesn't take a multivariate correlation to conclude that these two things are tightly related: If politicians care almost exclusively about the concerns of the rich, it makes sense that over the past decades they've enacted policies that have ended up benefiting the rich. And if you're not rich yourself, this is a problem. First and foremost, it's an economic problem because it's siphoned vast sums of money from the pockets of most Americans into those of the ultra wealthy. At the same time, relentless concentration of wealth and power among the rich is deeply corrosive in a democracy, and this makes it a profoundly political problem as well.

How did we get here? In the past, after all, liberal politicians did make it their business to advocate for the working and middle classes, and they worked that advocacy through the Democratic Party. But they largely stopped doing this in the '70s, leaving the interests of corporations and the wealthy nearly unopposed. The story of how this happened is the key to understanding why the Obama era lasted less than two years.

About a year ago, the Pew Research Center looked looked at the sources reporters used for stories on the economy. The White House and members of Congress were often quoted, of course. Business leaders. Academics. Ordinary citizens. If you're under 40, you may not notice anything amiss. Who else is missing, then? Well: "Representatives of organized labor unions," Pew found, "were sources in a mere 2% of all the economy stories studied."

It wasn't always this way. Union leaders like John L. Lewis, George Meany, and Walter Reuther were routine sources for reporters from the '30s through the '70s. And why not? They made news. The contracts they signed were templates for entire industries. They had the power to bring commerce to a halt. They raised living standards for millions, they made and broke presidents, and they formed the backbone of one of America's two great political parties.

They did far more than that, though. As historian Kim Phillips-Fein puts it, "The strength of unions in postwar America had a profound impact on all people who worked for a living, even those who did not belong to a union themselves." Wages went up, even at nonunion companies. Health benefits expanded, private pensions rose, and vacations became more common. It was unions that made the American economy work for the middle class, and it was their later decline that turned the economy upside-down and made it into a playground for the business and financial classes.

Technically, American labor began its ebb in the early '50s. But as late as 1970, private-sector union density was still more than 25 percent, and the absolute number of union members was at its highest point in history. American unions had plenty of problems, ranging from unremitting hostility in the South to unimaginative leadership almost everywhere else, but it wasn't until the rise of the New Left in the '60s that these problems began to metastasize.

The problems were political, not economic. Organized labor requires government support to thrive—things like the right to organize workplaces, rules that prevent retaliation against union leaders, and requirements that management negotiate in good faith—and in America, that support traditionally came from the Democratic Party. The relationship was symbiotic: Unions provided money and ground game campaign organization, and in return Democrats supported economic policies like minimum-wage laws and expanded health care that helped not just union members per se—since they'd already won good wages and benefits at the bargaining table—but the interests of the working and middle classes writ large.

But despite its roots in organized labor, the New Left wasn't much interested in all this. As the Port Huron Statement, the founding document of Students for a Democratic Society, famously noted, the students who formed the nucleus of the movement had been "bred in at least modest comfort." They were animated not by workplace safety or the cost of living, but first by civil rights and antiwar sentiment, and later by feminism, the sexual revolution, and environmentalism. They wore their hair long, they used drugs, and they were loathed by the mandarins of organized labor.

By the end of the '60s, the feeling was entirely mutual. New Left activists derided union bosses as just another tired bunch of white, establishment Cold War fossils, and as a result, the rupture of the Democratic Party that started in Chicago in 1968 became irrevocable in Miami Beach four years later. Labor leaders assumed that the hippies, who had been no match for either Richard Daley's cops or establishment control of the nominating rules, posed no real threat to their continued dominance of the party machinery. But precisely because it seemed impossible that this motley collection of shaggy kids, newly assertive women, and goo-goo academics could ever figure out how to wield real political power, the bosses simply weren't ready when it turned out they had miscalculated badly. Thus George Meany's surprise when he got his first look at the New York delegation at the 1972 Democratic convention. "What kind of delegation is this?" he sneered. "They've got six open fags and only three AFL-CIO people on that delegation!"

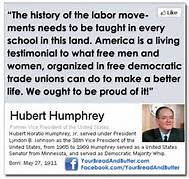

But that was just the start. New rules put in place in 1968 led by almost geometric progression to the nomination of George McGovern in 1972, and despite McGovern's sterling pro-labor credentials, the AFL-CIO refused to endorse him. Not only were labor bosses enraged that the hippies had thwarted the nomination of labor favorite Hubert Humphrey, but amnesty, acid, and abortion were simply too much for them. Besides, Richard Nixon had been sweet-talking them for four years, and though relations had recently become strained, he seemed not entirely unsympathetic to the labor cause. How bad could it be if he won reelection?

Plenty bad, it turned out—though not because of anything Nixon himself did. The real harm was the eventual disaffection of the Democratic Party from the labor cause. Two years after the debacle in Miami, Nixon was gone and Democrats won a landslide victory in the 1974 midterm election. But the newly minted members of Congress, among them former McGovern campaign manager Gary Hart, weren't especially loyal to big labor. They'd seen how labor had treated McGovern, despite his lifetime of support for their issues.

The results were catastrophic. Business groups, simultaneously alarmed at the expansion of federal regulations during the '60s and newly emboldened by the obvious fault lines on the left, started hiring lobbyists and launching political action committees at a torrid pace. At the same time, corporations began to realize that lobbying individually for their own parochial interests (steel, sugar, finance, etc.) wasn't enough: They needed to band together to push aggressively for a broadly pro-business legislative environment. In 1971, future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell wrote his now-famous memo urging the business community to fight back: "Strength lies in organization," he wrote, and would rise and fall "through joint effort, and in the political power available only through united action and national organizations." Over the next few years, the Chamber of Commerce morphed into an aggressive and highly politicized advocate of business interests, conservative think tanks began to flourish, and more than 100 corporate CEOs banded together to found a pro-market supergroup, the Business Roundtable.

They didn't have to wait long for their first big success. By 1978, a chastened union movement had already given up on big-ticket legislation to make it easier to organize workplaces. But they still had every reason to think they could at least win passage of a modest package to bolster existing labor law and increase penalties for flouting rulings of the National Labor Relations Board. After all, a Democrat was president, and Democrats held 61 seats in the Senate. So they threw their support behind a compromise bill they thought the business community would accept with only a pro forma fight.

Instead, the Business Roundtable, the US Chamber of Commerce, and other business groups declared war. Organized labor fought back with all it had—but that was no longer enough: The bill failed in the Senate by two votes. It was, said right-wing Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), "a starting point for a new era of assertiveness by big business in Washington." Business historian Kim McQuaid put it more bluntly: 1978, he said, was "Waterloo" for unions.

Organized labor, already in trouble thanks to stagflation, globalization, and the decay of manufacturing, now went into a death spiral. That decline led to a decline in the power of the Democratic Party, which in turn led to fewer protections for unions. Rinse and repeat. By the time both sides realized what had happened, it was too late—union density had slumped below the point of no return.

Why does this matter? Big unions have plenty of pathologies of their own, after all, so maybe it's just as well that we're rid of them. Maybe. But in the real world, political parties need an institutional base. Parties need money. And parties need organizational muscle. The Republican Party gets the former from corporate sponsors and the latter from highly organized church-based groups. The Democratic Party, conversely, relied heavily on organized labor for both in the postwar era. So as unions increasingly withered beginning in the '70s, the Democratic Party turned to the only other source of money and influence available in large-enough quantities to replace big labor: the business community. The rise of neo-liberalism in the '80s, given concrete form by the Democratic Leadership Council, was fundamentally an effort to make the party more friendly to business. After all, what choice did Democrats have? Without substantial support from labor or business, no modern party can thrive.

It's important to understand what happened here. Entire forests have been felled explaining why the working class abandoned the Democratic Party, but that's not the real story. It's true that Southern whites of all classes have increasingly voted Republican over the past 30 years. But working-class African Americans have been (and remain) among the most reliable Democratic voters, and as Larry Bartels has shown convincingly, outside the South the white working class has not dramatically changed its voting behavior over the past half-century. About 50 percent of these moderate-income whites vote for Democratic presidential candidates, and a bit more than half self-identify as Democrats. These numbers bounce up and down a bit (thus the "Reagan Democrat" phenomenon of the early '80s), but the overall trend has been virtually flat since 1948.

In other words, it's not that the working class has abandoned Democrats. It's just the opposite: The Democratic Party has largely abandoned the working class.

Here's why this is a big deal. Progressive change in the United States has always come in short, intense spurts: The Progressive Era lasted barely a decade at the national level, the New Deal saw virtually all of its legislative activity enacted within the space of six years between 1933 and 1938, and the frenzy of federal action associated with the '60s nearly all unfolded between 1964 and 1970. There have been exceptions, of course: The FDA was created in 1906, the GI Bill was passed in 1944, and the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990. And the courts have followed a schedule all their own. Still, one striking fact remains: Liberal reform is not a continuous movement powered by mere enthusiasm. Reform eras last only a short time and require extraordinarily intense levels of cultural and political energy to get started. And they require two other things to get started: a Democratic president and a Democratic Congress.

In 2008, fully four decades after our last burst of liberal change, we got that again. But instead of five or six tumultuous years, the surge of liberalism that started in 2008 lasted scarcely 18 months and produced only two legislative changes really worthy of note: health care reform and the repeal of Don't Ask, Don't Tell. By the summer of 2010 liberals were dispirited, political energy had been co-opted almost entirely by the tea party movement, and in November, Republicans won a crushing victory.

Why? The answer, I think, is that there simply wasn't an institutional base big enough to insist on the kinds of political choices that would have kept the momentum of 2008 alive. In the past, blue-collar workers largely took their cues on economic policy from meetings in union halls, and in turn, labor leaders gave them a voice in Washington.

This matters, as Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson argue in one of last year's most important books, Winner-Take-All Politics, because politicians don't respond to the concerns of voters, they respond to the organized muscle of institutions that represent them. With labor in decline, both parties now respond strongly to the interests of the rich—whose institutional representation is deep and energetic—and barely at all to the interests of the working and middle classes.

This has produced three decades of commercial and financial deregulation that started during the administration of a Democrat, Jimmy Carter, gained steam throughout the Reagan era, and continued under Bill Clinton. There were a lot of ways America could have responded to the twin challenges of '70s-era stagflation and the globalization of finance, but the policies we chose almost invariably ignored the stagnating wages of the middle class and instead catered to the desires of the super rich: hefty tax cuts on both high incomes and capital gains. Deregulation of S& Ls (PDF) that led to extensive looting and billions in taxpayer losses. Monetary policy focused excessively on inflation instead of employment levels. Tacit acceptance of asset bubbles as a way of maintaining high economic growth. An unwillingness to regulate financial derivatives that led to enormous Wall Street profits and contributed to the financial crisis of 2008. At nearly every turn, corporations and the financial industry used their institutional muscle to get what they wanted, while the working class sat by and watched, mostly unaware that any of this was even happening.

It's impossible to wind back the clock and see what would have happened if things had been different, but we can take a pretty good guess. Organized labor, for all its faults, acted as an effective countervailing power for decades, representing not just its own interests, but the interests of virtually the entire wage-earning class against the investor class. As veteran Washington Post reporter David Broder wrote a few years ago, labor in the postwar era "did not confine itself to bread-and-butter issues for its own members. It was at the forefront of battles for aid to education, civil rights, housing programs and a host of other social causes important to the whole community. And because it was muscular, it was heard and heeded." If unions had been as strong in the '80s and '90s as they were in the '50s and '60s, it's almost inconceivable that they would have sat by and accepted tax cuts and financial deregulation on the scale that we got. They would have demanded economic policies friendlier to middle-class interests, they would have pressed for the appointment of regulators less captured by the financial industry, and they would have had the muscle to get both.

And that means things would have been different during the first two years of the Obama era, too. Aside from the question of whether the crisis would have been so acute in the first place, a labor-oriented Democratic Party almost certainly would have demanded a bigger stimulus in 2009. It would have fought hard for "cramdown" legislation to help distressed homeowners, instead of caving in to the banks that wanted it killed. It would have resisted the reappointment of Ben Bernanke as Fed chairman. These and other choices would have helped the economic recovery and produced a surge of electoral energy far beyond Obama's first few months. And since elections are won and lost on economic performance, voter turnout, and legislative accomplishments, Democrats probably would have lost something like 10 or 20 seats last November, not 63. Instead of petering out after 18 months, the Obama era might still have several years to run.

This is, of course, pie in the sky. Organized labor has become a shell of its former self, and the working class doesn't have any institutional muscle in Washington. As a result, the Democratic Party no longer has much real connection to moderate-income voters. And that's hurt nearly everyone.

If unions had remained strong and Democrats had continued to vigorously press for more equitable economic policies, middle-class wages over the past three decades likely would have grown at about the same rate as the overall economy—just as they had in the postwar era. But they didn't, and that meant that every year, the money that would have gone to middle-class wage increases instead went somewhere else. This created a vast and steadily growing pool of money, and the chart below gives you an idea of its size. It shows how much money would have flowed to different groups if their incomes had grown at the same rate as the overall economy. The entire bottom 80 percent now loses a collective $743 billion each year, thanks to the cumulative effect of slow wage growth. Conversely, the top 1 percent gains $673 billion. That's a pretty close match. Basically, the money gained by the top 1 percent seems to have come almost entirely from the bottom 80 percent.

And what about those in the 80th to 99th percentile? They didn't score the huge payoffs of the superrich, but they did okay, basically keeping up with economic growth. Yet the skyrocketing costs of things like housing and higher education (PDF) make this less of a success story than it seems. And there's been a bigger cost as well: It turns out that today's upper-middle-class families lead a much more precarious existence than raw income figures suggest.

Jacob Hacker demonstrated this persuasively in The Great Risk Shift, which examined the ways in which financial risk has increasingly been moved from corporations and the government onto individuals. Income volatility, for example, has risen dramatically over the past 30 years. The odds of experiencing a 50 percent drop in family income have more than doubled since 1970, and this volatility has increased for both high school and college grads. At the same time, traditional pensions have almost completely disappeared, replaced by chronically underfunded 401(k) plans in which workers bear all the risk of stock market gains and losses. Home foreclosures are up (PDF), Americans are drowning in debt, jobs are less secure, and personal bankruptcies have soared (PDF). These developments have been disastrous for workers at all income levels.

This didn't all happen thanks to a sinister 30-year plan hatched in a smoke-filled room, and it can't be reined in merely by exposing it to the light. It's a story about power. It's about the loss of a countervailing power robust enough to stand up to the influence of business interests and the rich on equal terms. With that gone, the response to every new crisis and every new change in the economic landscape has inevitably pointed in the same direction. And after three decades, the cumulative effect of all those individual responses is an economy focused almost exclusively on the demands of business and finance. In theory, that's supposed to produce rapid economic growth that serves us all, and 30 years of free-market evangelism have convinced nearly everyone—even middle-class voters who keep getting the short end of the economic stick—that the policy preferences of the business community are good for everyone. But in practice, the benefits have gone almost entirely to the very wealthy.

It's not clear how this will get turned around. Unions, for better or worse, are history. Even union leaders don't believe they'll ever regain the power of their glory days. If private-sector union density increased from 7 percent to 10 percent, that would be considered a huge victory. But it wouldn't be anywhere near enough to restore the power of the working and middle classes.

And yet: The heart and soul of liberalism is economic egalitarianism. Without it, Wall Street will continue to extract ever vaster sums from the American economy, the middle class will continue to stagnate, and the left will continue to lack the powerful political and cultural energy necessary for a sustained period of liberal reform. For this to change, America needs a countervailing power as big, crude, and uncompromising as organized labor used to be.

But what?

Over the past 40 years, the American left has built an enormous institutional infrastructure dedicated to mobilizing money, votes, and public opinion on social issues, and this has paid off with huge strides in civil rights, feminism, gay rights, environmental policy, and more. But the past two years have demonstrated that that isn't enough. If the left ever wants to regain the vigor that powered earlier eras of liberal reform, it needs to rebuild the infrastructure of economic populism that we've ignored for too long. Figuring out how to do that is the central task of the new decade.

Here's the saddest thing,

Trump is the president elect.

And This is his BOSS

How Democrats Went From Being the ‘Party of the People’ to the Party of Rich ElitesDemocrats have gone from the party of the New Deal to a party that is defending mass inequality. By Tobita Chow

The Democratic Party was once the party of the New Deal and the ally of organized labor. But by the time of Bill Clinton's presidency, it had become the enemy of New Deal programs like welfare and Social Security and the champion of free trade deals. What explains this apparent reversal? Thomas Frank—best known for his analysis of the Republican Party base in What's the Matter with Kansas?—attempts to answer this question in his latest book, Listen Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?

According to Frank, popular explanations which blame corporate lobby groups and the growing power of money in politics are insufficient. Frank instead points to a decision by Democratic Party elites in the 1970s to marginalize labor unions and transform from the party of the working class to the party of the professional class. In so doing, the Democratic Party radically changed the way it understood social problems and how to solve them, trading in the principle of solidarity for the principle of competitive individualism and meritocracy. The end result is that the party which created the New Deal and helped create the middle class has now become “the party of mass inequality.” In These Times spoke with Frank recently about the book via telephone.

The book is about how the Democratic Party turned its back on working people and now pursues policies that actually increase inequality. What are the policies or ideological commitments in the Democratic Party that make you think this?

The first piece of evidence is what’s happened since the financial crisis. This is the great story of our time. Inequality has actually gotten worse since then, which is a remarkable thing. This is under a Democratic president who we were assured (or warned) was the most liberal or radical president we would ever see. Yet inequality has gotten worse, and the gains since the financial crisis, since the recovery began, have gone entirely to the top 10 percent of the income distribution.

This is not only because of those evil Republicans, but because Obama played it the way he wanted to. Even when he had a majority in both houses of Congress and could choose whoever he wanted to be in his administration, he consistently made policies that favored the top 10 percent over everybody else. He helped out Wall Street in an enormous way when they were entirely at his mercy.

He could have done anything he wanted with them, in the way that Franklin Roosevelt did in the ’30s. But he chose not to.

Why is that? This is supposed to be the Democratic Party, the party that’s interested in working people, average Americans. Why would they react to a financial crisis in this way? Once you start digging into this story, it goes very deep. You find that there was a transition in the Democratic Party in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s where they convinced themselves that they needed to abandon working people in order to serve a different constituency: a constituency essentially of white-collar professionals.

That’s the most important group in their coalition. That’s who they won over in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. That’s who they serve, and that’s where they draw from. The leaders of the Democratic Party are always from this particular stratum of society.

A lot of progressives that I talk to are pretty familiar with the idea that the Democratic Party is no longer protecting the interests of workers, but it’s pretty common for us to blame it on mainly the power of money in politics. But you start the book in chapter one by arguing there’s actually something much deeper going on. Can you say something about that?

Money in politics is a big part of the story, but social class goes deeper than that. The Democrats have basically made their commitment [to white-collar professionals] already before money and politics became such a big deal. It worked out well for them because of money in politics. So when they chose essentially the top 10 percent of the income distribution as their most important constituents, that is the story of money.

It wasn’t apparent at the time in the ’70s and ’80s when they made that choice. But over the years, it has become clear that that was a smart choice in terms of their ability to raise money. Organized labor, of course, is no slouch in terms of money. They have a lot of clout in dollar terms. However, they contribute and contribute to the Democrats and they almost never get their way—they don’t get, say, the Employee Free Choice Act, or Bill Clinton passes NAFTA. They do have a lot of money, but their money doesn’t count.

All of this happened because of the civil war within the Democratic Party. They fought with each other all the time in the ’70s and the ’80s. One side hadn’t completely captured the party until Bill Clinton came along in the ’90s. That was a moment of victory for them.

Bill Clinton’s presidency is what progressives usually cite as the time when things went bad. But there’s a trend that goes back to the ’70s, right?

Historians always cite the ’68 election as the turning point. The party was torn apart by the controversy over the Vietnam war, protesters were in the streets in Chicago and the Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey went on to lose. Democrats thought this was terrible, and it was. So they set up a commission to reorganize the party, the McGovern Commission.

The McGovern Commission basically set up our modern system of primaries. Before the commission, we didn’t have these long primary contests in state after state after state. Primaries are a good thing, as were most things the McGovern Commission did.

But they also removed organized labor from its structural position of power in the Democratic Party. There was a lot of resentment towards labor during the Vietnam War. A lot of unions took President Johnson’s side on Vietnam. There was also this sense—which I think was correct at the time—that labor was a dinosaur, that it was out of touch and undemocratic and very white.

There were a lot of reasonable objections to organized labor at the time. The problem is, when you get rid of labor in your party, you also get rid of issues that matter to working people. That’s the basic mistake that Democrats made in the ’70s. Of course, labor still is a big part of the Democratic coalition—it gives them their money, it helps out at election time in a huge way. But unions no longer have the presence in party councils that they used to. That disappeared.

One of the most shocking quotes in the book is from Alfred Kahn, an advisor to Jimmy Carter, who said, “I’d love the Teamsters to be worse off. I’d love the automobile workers to be worse off.” He then basically says that unionized workers are exploiting other workers.

Isn’t that amazing? He’s describing a situation in the 1970s. There was all this controversy in the 1970s about labor versus management—this was the last decade where those fights were front and center in our national politics. And he’s coming down squarely on the side of management in those fights.

And remember, Kahn was a very important figure in the Carter administration. The way that he describes unions is incorrect—he’s actually describing professionals. Professionals are a protected class that you can’t do anything about—they’re protected by the laws of every state that dictate who can practice in these fields. It’s funny that he projects that onto organized labor and holds them responsible for the sins of another group.

This is a Democrat in an administration that is actually not very liberal. This is the administration that carried out the first of the big de-regulations. This is the administration that had the great big capital gains tax cuts, that carried out the austerity plan that saw the Federal Reserve jack its interest rates sky high. They clubbed the economy to the ground in order to stop “wage inflation,” in which workers, if they have enough power, can keep demanding higher wages. It was incredible.

What’s the content of the ideology of the professional class and how does it hurt working people? What are their guiding principles?

The first commandment of the professional class is the idea of meritocracy, which allows people to think that those on top are there because they deserve to be. With the professional class, it’s always associated with education. They deserve to be there because they worked really hard and went to a good college and to a good graduate school. They’re high achievers. Democrats are really given to credentialism in a way that Republicans aren’t.

If you look at the last few Democratic presidents, Bill Clinton and Obama, and Hillary Clinton as well, their lives are a tale of educational achievement. This is what opened up the doors of the world to them. It’s a party of who people who have gotten where they are by dint of educational accomplishment.

This produces a set of related ideas. When the Democrats, the party of the professionals, look at the economic problems of working-class people, they always see an educational problem, because they look at working class people and say, “Those people didn’t do what I did”: go and get advanced degrees, go to the right college, get the high SAT scores and study STEM or whatever.

There’s another interesting part of this ideology: this endless search for consensus. Washington is a city of professionals with advanced degrees, and Democrats look around them there and say, “We’re all intelligent people. We all went to good schools. We know what the problems are and we know what the answers are, and politics just get in the way.”

This is a very typical way of thinking for the professional class: reaching for consensus, because politics is this ugly thing that you don’t really need. You see this in Obama’s endless efforts to negotiate a grand bargain with Republicans because everybody in Washington knows the answers to the problems—we just have to get together, sit down and make an agreement. The same with Obamacare: He spent so many months trying to get Republicans to sign on, even just one or two, so that he could say it was bipartisan. It was an act of consensus. And the Republicans really played him, because they knew that’s what he’d do.

To go back to your point about education: At one point you quote Arne Duncan, who was Obama’s secretary of education, saying that the only way to end poverty is through education. Why can’t that work?

The big overarching problem of our time is inequality. If you look at historical charts of productivity and wage growth, these two things went hand in hand for decades after World War II, which we think of as a prosperous, middle-class time when even people with a high school degree, blue-collar workers, could lead a middle class life. And then everything went wrong in the 1970s. Productivity continued to go up and wage growth stopped. Wage growth has basically been flat ever since then. But productivity goes up by leaps and bounds all the time. We have all of these wonderful technological advances. Workers are more productive than ever but they haven’t benefited from it. That’s the core problem of inequality.

Now, if the problem was that workers weren’t educated enough, weren’t smart enough, productivity would not be going up. But that productivity line is still going up. So we can see that education is not the issue.

It’s important that people get an education, of course. I spent 25 years of my life getting an education. It’s basic to me. It’s a fundamental human right that people should have the right to pursue whatever they want to the maximum extent of their individual potential. But the idea that this is what is holding them back is simply incorrect as a matter of fact. What’s holding them back is that they don’t have the power to demand higher wages.

If we talk about the problem as one of education rather than power, then the blame goes back to these workers. They just didn’t go out and work hard and do their homework and get a gold star from their teacher. If you take the education explanation for inequality, ultimately you’re blaming the victims themselves.

Unfortunately, that is the Democratic view. That’s why Democrats have essentially become the party of mass inequality. They don’t really have a problem with it.

So really, the solution would have to be solidarity and organized power.

That was an essential point that I try to make in Listen Liberal: that there is no solidarity in a meritocracy. A meritocracy really is every man for himself.

Don’t get me wrong. People at the top of the meritocracy, professionals, obviously have enormous respect for one another. That is the nature of professional meritocracy. They have enormous respect for the people at the top, but they feel very little solidarity for people beneath them who don’t rise in the meritocracy.

Look at the white-collar workplace. If some professional gets fired, the other professionals don’t rally around and go on strike or protest or something like that. They just don’t do that. They feel no solidarity because everything goes back to you and whether or not you’ve made the grade. If somebody gets fired, they must’ve deserved it somehow.

I have my own personal experience. Look at academia over the last 20 years. They’re cranking out these Ph.D.s in the humanities who can’t get jobs on tenure track and instead have to work as adjuncts for very low pay, no benefits. One of the fascinating parts about this is that, with a few exceptions, the people who do have tenure-track jobs and are at the top of their fields, do very little about what’s happened to their colleagues who work as adjuncts. Essentially this is the Uberizing of higher education. The professionals who are in a position of authority have done almost nothing about it. There are academics here and there who feel bad about what’s happened to adjuncts and do say things about it, but by and large, overall, there is no solidarity in that meritocracy. They just don’t care.

Do you think there’s a connection between the fact that the Democratic Party has turned against workers and the rise of Donald Trump?

Yes. Because if you look at the polling, Trump is winning the votes of a lot of people who used to be Democrats. These white, working-class people are his main base of support. As a group, these people were once Democrats all over the country. These are Franklin Roosevelt’s people. These are the people that the Democrats essentially decided to turn their backs on back in the 1970s. They call them the legatees of the New Deal. They were done with these guys, and now look what’s happened—they’ve gone with Donald Trump. That’s frightening and horrifying.

But Trump talks about their issues in a way that they find compelling, especially the trade issue. When he talks about trade, they believe him. Ironically, he’s saying the same things that Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders are saying about trade, but for whatever reason people find him more believable on this subject than they do Hillary Clinton.

Do you think that the rise of the Bernie campaign could herald a new era in the history of the Democratic Party?

I hope so. Both Trump and Bernie are turning their respective parties upside down. What Bernie is doing is very impressive. I interviewed him a few years ago and have always admired him. I think he’s a great man. To think that he could beat a Clinton in a Democratic primary anywhere in this country, let alone many primaries, was unthinkable a short time ago. And he’s done it without any Wall Street or big-business backing. That is extraordinary. It shows the kind of desperation that’s out there.

He has shown the way, and whether he gets the nomination or not (he won’t), there’ll be another Bernie four years from now. And there’ll also be another Trump. The Republican Party is being turned on its head much more violently than the Democrats. I live in Washington, D.C., and I spend time around Hillary-style Democrats. They really think that they’ve got this thing in the bag. And I don’t just mean her versus Bernie. I mean the Democratic Party winning the presidency for the rest of our lives. From here to eternity. They can choose whoever they want. They could nominate anybody and they would win. They think they’re in charge. When will they wake up?

One of your villains from the ’70s is Frederick Dutton, who wrote a book about how the Democratic Party needed to realign itself. You have a quote from him saying, “Every major realignment in U.S. political history has been accompanied by the coming of a large new group into the electorate.” You’re very critical of how he uses that idea in the ‘70s. But if you look at the newer voters attached to the Bernie campaign, it looks like the Democratic Party is experiencing something like that now.

Yes, in both cases you’re talking about a generational shift. That’s what he meant in 1971. He was talking about the counterculture and the “Now Generation” and the idea that they would come into the electorate and demand a different kind of politics—specifically his kind of politics.

Everybody always sees this new group that’s coming in as supporting what they want. That’s what he thought. I have a certain amount of contempt for that. Many years ago I wrote a book about the counterculture and how it was used for this purpose—specifically by the advertising industry. But Bernie’s doing the same thing. He’s using it for his own purposes.

Millenials’ take on the world is fascinating. Just a few years ago, people thought of them as very different. But now they’re coming out of college with enormous student debt, and they’re discovering that the job market is casualized and Uberized. The work that they do is completely casual. The idea of having a middle-class lifestyle in that situation is completely off the table for them.

Every time I think about these people, it burns me up. It makes me so angry what we’ve done to them as a society. It really gives the lie to Democratic Party platitudes about the world an education will open up for you. That path just doesn’t work anymore. Millenials can see that in their own lives very plainly.

So I’m very excited that they’re pro-Bernie. They really are the future. The Democrats would go on to make Hillary their champion and then get the stuffins kicked out of them. Who would have

thought Trump would win?

ACV Democratic News

ACVDN

No comments:

Post a Comment